The first tornadoes of the 2024 season have already left a trail from coast-to-coast, with tornadoes reported in California to Florida, including the first February tornado on record in the state of Wisconsin. The season is off to a rather interesting start, but where do we go from here?

Tornadoes surveyed so far in 2024 by the National Weather Service.

This year there are numerous factors to contend with in terms of forecasting a threat of tornadoes. One of the biggest drivers will be the transition from El Nino to La Nina which is currently forecast to occur.

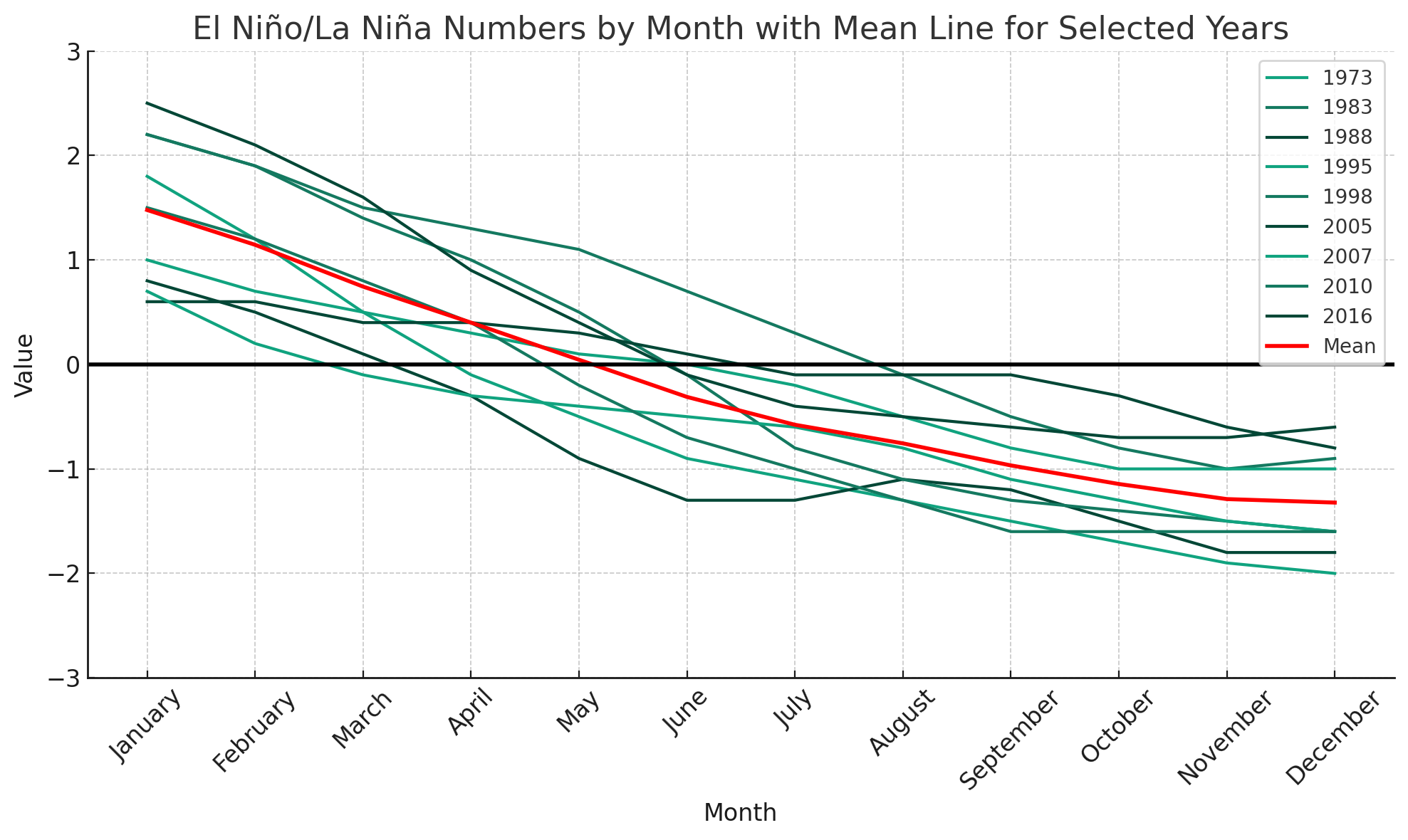

Long-range forecast models show neutral conditions taking over around May, June and July with La Nina conditions possible by July, August into September. The current NOAA forecasts have a nearly 80-percent chance of Neutral conditions by mid-year and a nearly 60-percent chance of La Nina later this year.

Years since 1950 moving from El Nino to La Nina.

Since 1950 there have been nine years in which ENSO moved from El Nino to La Nina: 1973, 1983, 1988, 1995, 1998, 2005, 2007, 2010 and 2016. I will be using these years as my analog going forward for forecasting potential trends.

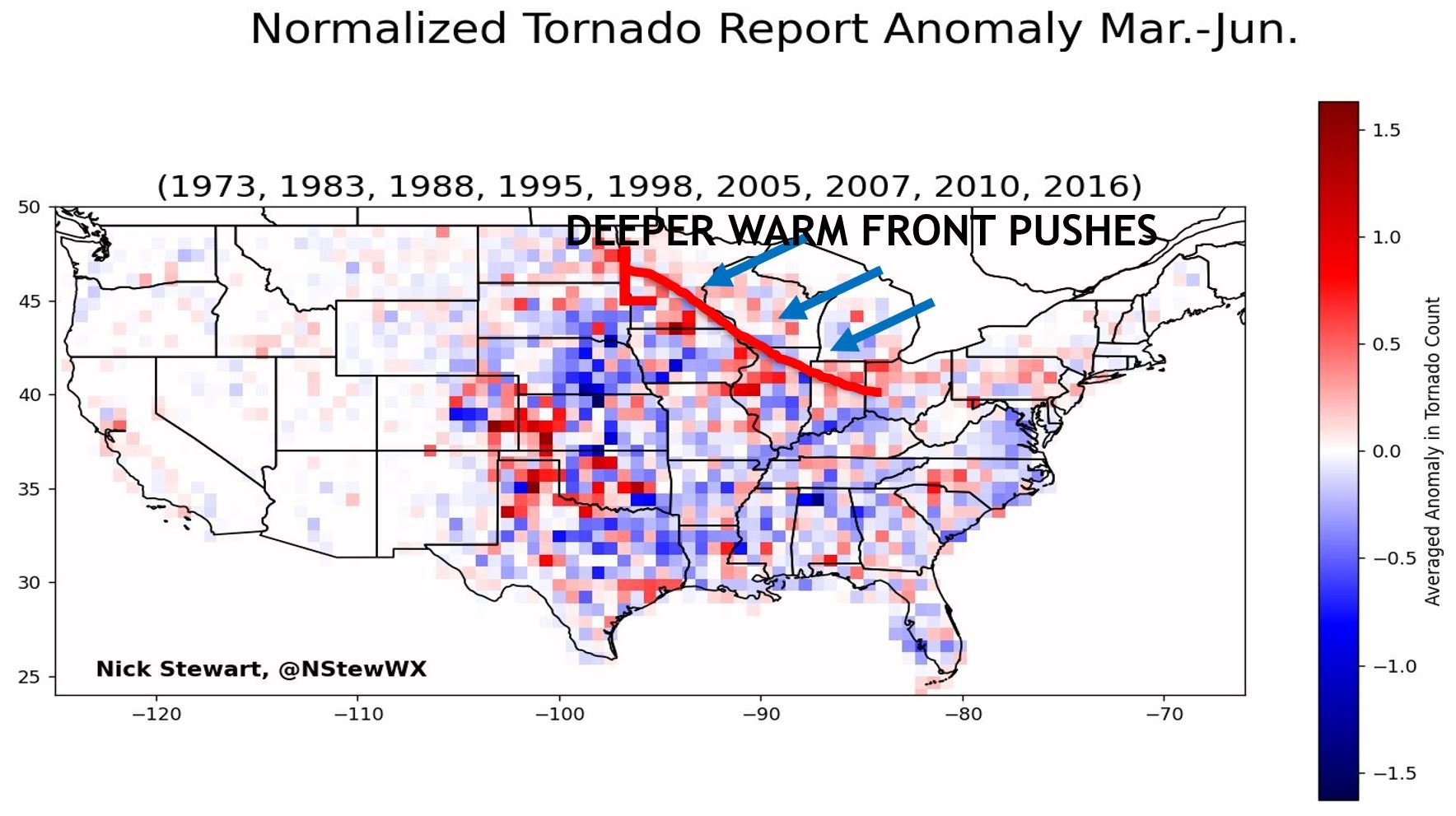

Normalized tornado reports compared to normal in the selected analog years.

Jumping straight into normalized springtime tornadoes compared to normal during the selected analog years, two areas really stand out to me in terms of above-normal tornado activity. First, the Central Plains including western Kansas, eastern Colorado and northern Texas.

Another area of interest includes southern Minnesota, eastern Iowa, northern Illinois, northern Indiana and northern Ohio.

Another interesting note is a lower anomaly in Dixie Alley from eastern Texas through Georgia.

Doing a reanalysis of the 500mb geopotential height anomaly shows a below-normal bullseye across the western and central CONUS. This could be a signal for more troughing ejecting into the central US which is a prerequisite for severe weather and storms on the Plains.

A reanalysis on precipitation rate anomaly also shows higher-than-normal precipitation across the central US during this period of Spring. While higher precipitation does not mean severe weather, the timing in spring makes it a high possibility.

Creating my own reanalysis using ERA5 data show a similar story with higher-than-normal precipitation across Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma and Texas compared to the 1991-2020 30-year mean. This shows the likelihood of active weather in the Central US using my analog years. Again, this could indicate severe weather potential.

Shifting focus to the Midwest and Great Lakes regions, an important thing to consider is the record-minimum ice coverage on the Great Lakes as of Feb. 17. A single-digit percentage of the Great Lakes are covered with ice which is wild, considering the historical average is close to 40 percent.

Looking back at tornado climatology, the higher springtime tornado maximums in the Minnesota through Ohio line could potentially be attributed to warm fronts being able to push deeper into the Great Lakes region when an otherwise cold Great Lakes would help keep the warm fronts at bay with a stiff east/northeast wind.

With less ice, the waters can warm up faster. This is, of course, dependent on a number of other factors but is at least one point of consideration.

What’s actually rather interesting is that of the nine years I’m using as analogs, six are well-below-normal ice coverage years with two years being near-normal. Only one of the years was slightly above normal.

I think this might be another research project for me with a hyper focus in the Midwest and Great Lakes region.

Finally looking at the Gulf of Mexico briefly, two things are in consideration this year. Near-shore waters are running below normal which could explain some of the tornado minimums in Dixie Alley.

Wider scale shows above-normal water temperatures which again could lead to better moisture advection deeper into spring for the central Plains.

Climate Prediction Center springtime precipitation outlook.

I’ll end with the official springtime forecast from the Climate Prediction Center which shows a wetter-than-normal season across the Central Plains and eastern US, with the highest chances in the southeast which is a pretty strong El Nino signal… for now.

-Meteorologist Nick Stewart